Part 2: COVID-19 Variants

As of 16th July 2021, there have been over 189,072,198 cases worldwide, with more than 4,069,212 confirmed deaths, affecting 223 countries. The positive though is that there has been a rapid influx of the number of vaccine doses administered across the world. Today according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre there have been a total of 3,559,010,516 vaccine doses administered to aid in this fight against COVID-19.

While the world races to get as many people fully vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, a new challenge is beginning to arise- the possibility of rapid virus mutations and variations that could possibly alter the course of our race to end COVID-19.

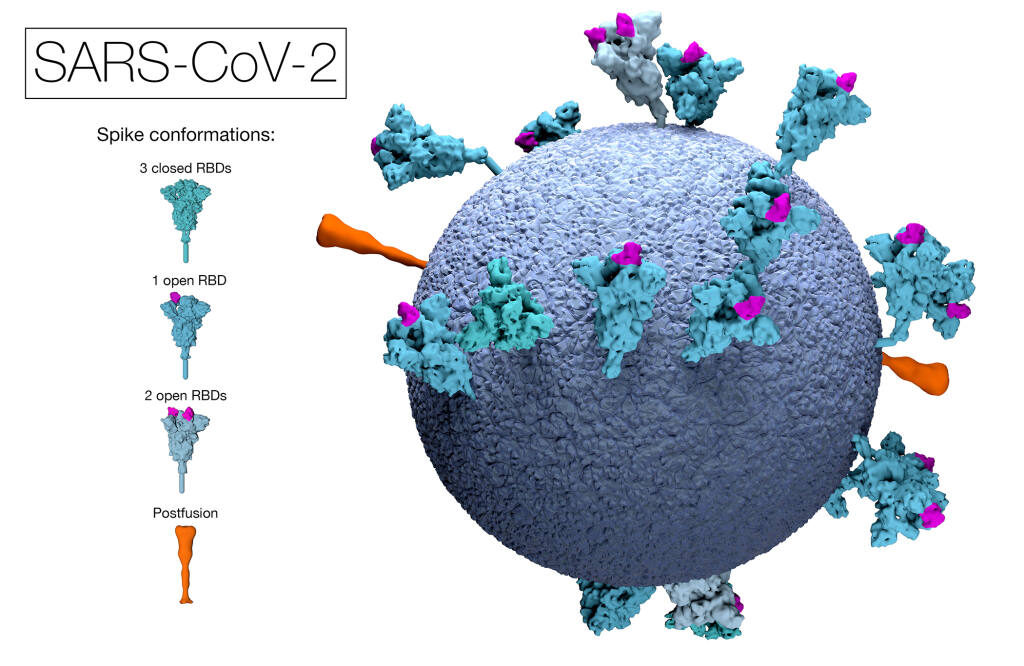

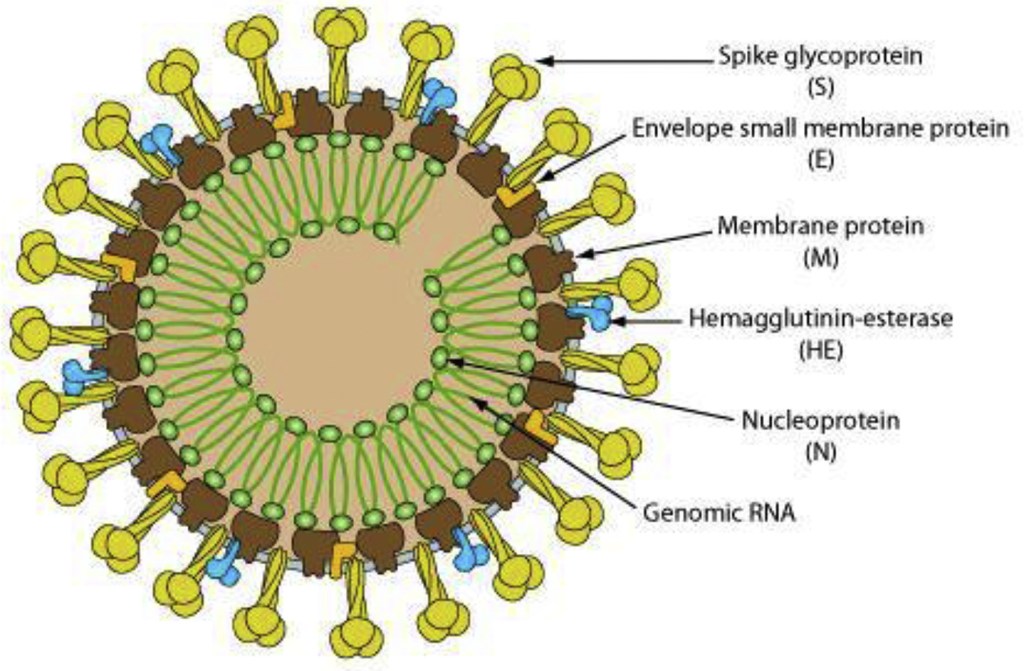

The intricate structure of viruses.

Genome sequencing – the process by which the entirety, or nearly the entirety, of the DNA sequence of an organism’s genome, is determined at a single time.

Genomic information has been instrumental in identifying inherited disorders, characterizing the mutations that drive organism progression, and tracking disease outbreaks. This process has played a fundamental role in our understanding of COVID-19.

The sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 has been taking place since the beginning of the pandemic, tracking and understanding its viral evolution and enabling genomic epidemiology investigations into its origins and spread.

SARS-CoV-2 is a spherical positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus that is approximately 30kb long making it one of the largest genomes amongst RNA viruses. It is reported to contain about 14 open reading frames encoding 27 proteins.

Open Reading frame is a term that is used to refer to a frame of reference in a genome, and what is being read is the RNA code that is used to make the necessary proteins pertaining to the genome. The “open” part means that the path through which the ribosome reads the RNA code remains open and as a result can continue to add the necessary amino acids one after another when forming the genome structure.

This entire process of genome sequencing has allowed us to not only understand the entire structure of SARS-CoV-2 but has allowed us to further track and monitor variations and mutations in its structure. This has led to the rapid identification of the first of a number of variants of concern (VOCs) in late 2020, where genome changes were having observable impacts on virus biology and disease transmission.

Variant origins

In order to understand how variations in a virus’ structure occur, we must dive deeper into the main goal of any virus: to multiply itself.

Nearly all processes in the body involve proteins. Your body’s DNA sequence contains instructions on how to make up most of the proteins in your body. This happens through a single strand of the DNA sequence in your body known as messenger RNA or mRNA that contains instructions on how to manufacture a particular type of protein your body needs. This mRNA strand is read by your body’s cells and they proceed to make that protein.

It is through this process that the COVID-19 virus works. When the virus enters your body, the mRNA sequence of letters that make up its structure is read and copied by your cells. This sequence of letters in the mRNA strand instructs your body’s cells on how to manufacture and multiply the COVID-19 virus. This allows the virus to ‘hijack’ your body and subdue it.

The problem though is that this is an entirely random process, as the cells are divided and multiplied. This means that errors can occur when your body’s cells read the mRNA sequence of letters when preparing to manufacture the virus. These errors can be the deletion, addition, or swapping of letters in the mRNA sequence of instructions. These mistakes are referred to as mutations and are the main cause of the variations we are seeing in the COVID-19 virus.

Naturally, because your body utilizes double helix DNA strands to manufacture all the cells in your body, it is equipped with a proofreading and repair tool. This tool allows the body to identify mutations within the DNA instructions on how to manufacture a particular cell and fixes it right away.

However, this process is not perfect and some rapid permanent mutations and uncontrollable cell divisions could in turn harm your body. When multiple mutations in division-related genes accumulate in the same cell cancers begins to develop.

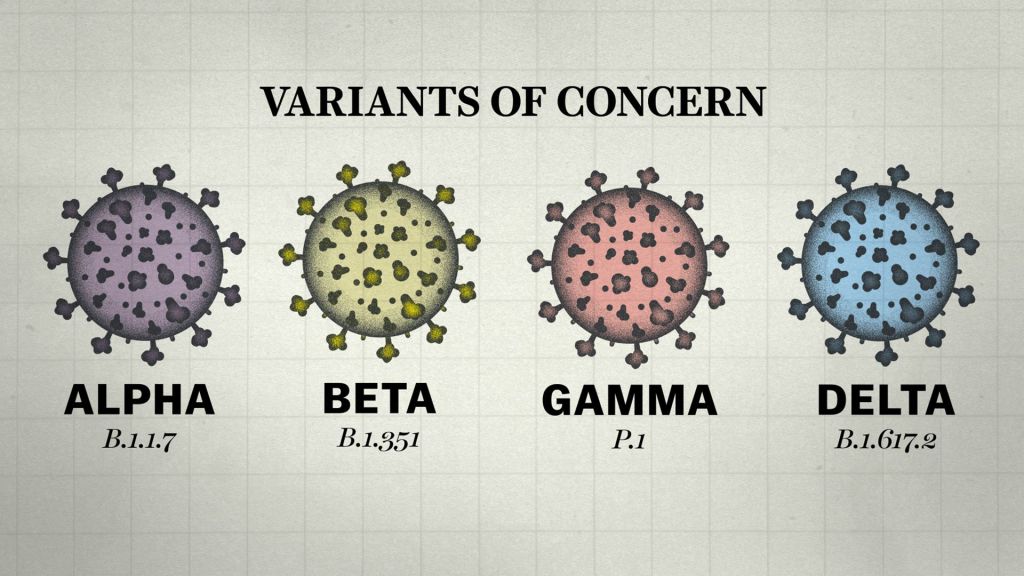

Variants of Concern(VOCs)

Across all virus genomes sequenced to date, thousands of mutations have emerged since the start of the pandemic, which in turn have given rise to thousands of different variants.

The majority of these mutations have had no perceivable impact on the virus or disease biology and have in fact made the virus weaker while others have greatly changed the way the virus behaves and infects your body. These variants in the latter category have been identified and have appeared to increase transmissibility, and potentially have an impact on disease severity. As a result, they have been labeled VOCs.

Thankfully due to genomic sequencing and data analysis these evolutions in the structure of the COVID-19 virus have been tracked and are being studied in order to understand how they are changing the course of the pandemic.

Below is a brief breakdown of each of the VOCs:

The established nomenclature systems for naming and tracking SARS-CoV-2 genetic lineages by GISAID, Nextstrain and Pango are currently and will remain in use by scientists and in scientific research. To assist with public discussions of variants, WHO convened a group of scientists from the WHO Virus Evolution Working Group, the WHO COVID-19 reference laboratory network, representatives from GISAID, Nextstrain, Pango, and additional experts in virological, microbial nomenclature and communication from several countries and agencies to consider easy-to-pronounce and non-stigmatizing labels for VOI and VOC. At the present time, this expert group convened by WHO has recommended using letters of the Greek Alphabet, i.e., Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta which will be easier and more practical to discussed by non-scientific audiences.

Naming SARS-CoV-2 variants – WHO

Alpha Variant

In the UK, the B.1.1.7 Alpha variant was first identified as a VOC by COG-UK in December 2020, as it was increasing in frequency during a nationwide lockdown, whilst other variants were decreasing in frequency. A retrospective examination of the data determined that the variant had been in circulation since September, but at that time there were insufficient data to suggest that it was a VOC.

The B.1.1.7 variant is currently the most highly sequenced and well-characterized VOC and has been shown to have increased levels of transmissibility at a rate of between 40 and 70%. In addition, the results from several preliminary analyses of B.1.1.7, suggest that there could be an increase in mortality rates as a result of the variant. The COG-UK mutation tracker outlines the spike protein mutations seen circulating in the UK. It also details the scientific evidence to date on the impact of different mutations on immune evasion.

Beta Variant

In South Africa, the B.1.351 Beta variant was identified after frontline clinicians alerted NGS-SA to a rapid increase in cases, which prompted a genomic investigation. The B.1.351 variant is a concern as it has been shown to have increased transmissibility and to reduce the efficacy of some vaccines.

Gamma Variant

In the case of the P.1 Gamma variant, Japan reported the variant via their surveillance system, after detection in four travellers who had returned from Brazil. The variant was flagged to be of concern due to the presence of spike mutations also found in the B.1.351 variant: N501Y (which increases virus binding affinity to the ACE2 receptor on human cells), E484K (which renders the virus less susceptible to some monoclonal antibodies) and K417N/T (suggested to increase binding affinity to ACE2, in combination with N501Y). The set of mutations/deletions, especially N501Y, shared between the P.1, B.1.1.7, and the B.1.351 variants appear to have arisen independently.

P.1 and B.1.351 also appear to be associated with a rapid increase in cases in locations where COVID-19 disease rates were previously high. Therefore, it will be crucial to investigate whether there is an increased rate of recent re-infection, caused by these variants, in previously exposed healthy individuals.

Delta Variant

The latest addition to this list of VOCs is the B.1.617.2 Delta variant. The Delta variant was first identified in India in December 2020 and led to major outbreaks in the country. It has been categorized as a double mutant because it contains two critical mutations L452R (which makes the virus more transmissible – first identified in the Epsilon B.1.427/429 variants) and E484Q(a version of the E484K mutation found in the P1 and Gamma Variants that makes it easier for the virus to re-infect people who already had COVID-19).

It then spread rapidly and is now reported in 104 countries, according to a CDC tracker. As of early July, Delta has become the dominant form of the coronavirus in the U.S., U.K., Germany, and other countries. In the U.K., for instance, the Delta variant now makes up more than 97% of new COVID-19 cases, according to Public Health England.

The strain has mutations on the spike protein that make it easier for it to infect human cells. That means people may be more contagious if they contract the virus and more easily spread it to others.

In fact, researchers have said that the Delta variant is about 50% more contagious than the Alpha variant, which was first identified in the U.K. Alpha, also known as B.1.1.7, was already 50% more contagious than the original coronavirus first identified in China in 2019.

Public health experts estimate that the average person who gets infected with Delta spreads it to three or four other people, as compared with one or two other people through the original coronavirus strain, according to Yale Medicine. The Delta variant may also be able to escape protection from vaccines and some COVID-19 treatments, though studies are still ongoing.

What about Variants of Interest and Variants of High Consequence?

According to the WHO, Variants of Interest (VOIs) are defined to be:

- with genetic changes that are predicted or known to affect virus characteristics such as transmissibility, disease severity, immune escape, diagnostic or therapeutic escape; AND

- Identified to cause significant community transmission or multiple COVID-19 clusters, in multiple countries with increasing relative prevalence alongside increasing number of cases over time, or other apparent epidemiological impacts to suggest an emerging risk to global public health.

At the moment these are the only VOIs under investigation:

As for Variants of High Consequence, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) :

A variant of high consequence has clear evidence that prevention measures or medical countermeasures (MCMs) have significantly reduced effectiveness relative to previously circulating variants.

Possible attributes of a variant of high consequence:

In addition to the possible attributes of a variant of concern

- Impact on Medical Countermeasures (MCM)

- Demonstrated failure of diagnostics

- Evidence to suggest a significantly reduction in vaccine effectiveness, a disproportionately high number of vaccine breakthrough cases, or very low vaccine-induced protection against severe disease

- Significantly reduced susceptibility to multiple Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) or approved therapeutics

- More severe clinical disease and increased hospitalizations

A variant of high consequence would require notification to WHO under the International Health Regulations, reporting to CDC, an announcement of strategies to prevent or contain the transmission, and recommendations to update treatments and vaccines.

Currently, there are no SARS-CoV-2 variants that rise to the level of high consequence.

Why are several variants showing up now and what is the solution?

The simple reason that several variants are showing up now, can be found in the numbers. Today only a small fraction of the world population has been vaccinated against COVID-19. This is worrying because the only way we can combat the virus is by vaccinating as many people and slowing down the spread of the virus. The longer the virus continues to exist amongst large populations, the more opportunities the virus will get to find a solution to overcoming the challenge we are presenting it through our vaccines. This will mean that new and stronger SARS-CoV-2 variants could emerge that will be more robust and capable of dodging our immune defenses and possibly rendering our vaccines useless. The only way we can conquer this pandemic is to inoculate everyone.

Resources and Citations

COVID-19 Map – Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center

Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants – WHO

SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions -CDC

DNA proofreading and repair – Khan Academy

What You Need to Know About the Delta Variant – WebMD

Citations/References:

- Rambaut, A., Holmes, E. C., O’Toole, A., et al. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat Microbiol. 2020. 5(11): pp. 1403-1407.

- Callaway, E. ‘A bloody mess’: Confusion reigns over naming of new COVID variants. Nature. 2021;

- The COVID-19 UK Genomics Consortium COG-UK. 2021;

- Network for Genomic Surveillance in South Africa. KRISP. 2021;

- Volz, E., Mishra, S., Chand, M., et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B.1.1.7 in England:Insights from linking epidemiological and genetic data. medRxiv. 2021. p.10.1101/2020.12.30.20249034.

- NERVTAG paper on COVID-19 variant of concern B.1.1.7. Department of Health and Social Careand SAGE. 2021;

- Burki, T. Understanding variants of SARS-CoV-2. The Lancet. 2021. 397(10273): p. 462.

- COG-UK mutation explorer. COG-UK Consortium 2021;

- Weston, S., Frieman, M. B. COVID-19: Knowns, Unknowns, and Questions. mSphere. 2020. 5(2): pp. e00203-20.

- Khan, S., Siddique, R., Shereen, M. A., et al. Emergence of a Novel Coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2: Biology and Therapeutic Options. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2020. 58(5): pp. e00187-20.

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. World Health Organisation. 2020